Miles

Well-known member

- Mar 18, 2019

- 2,455

- 0

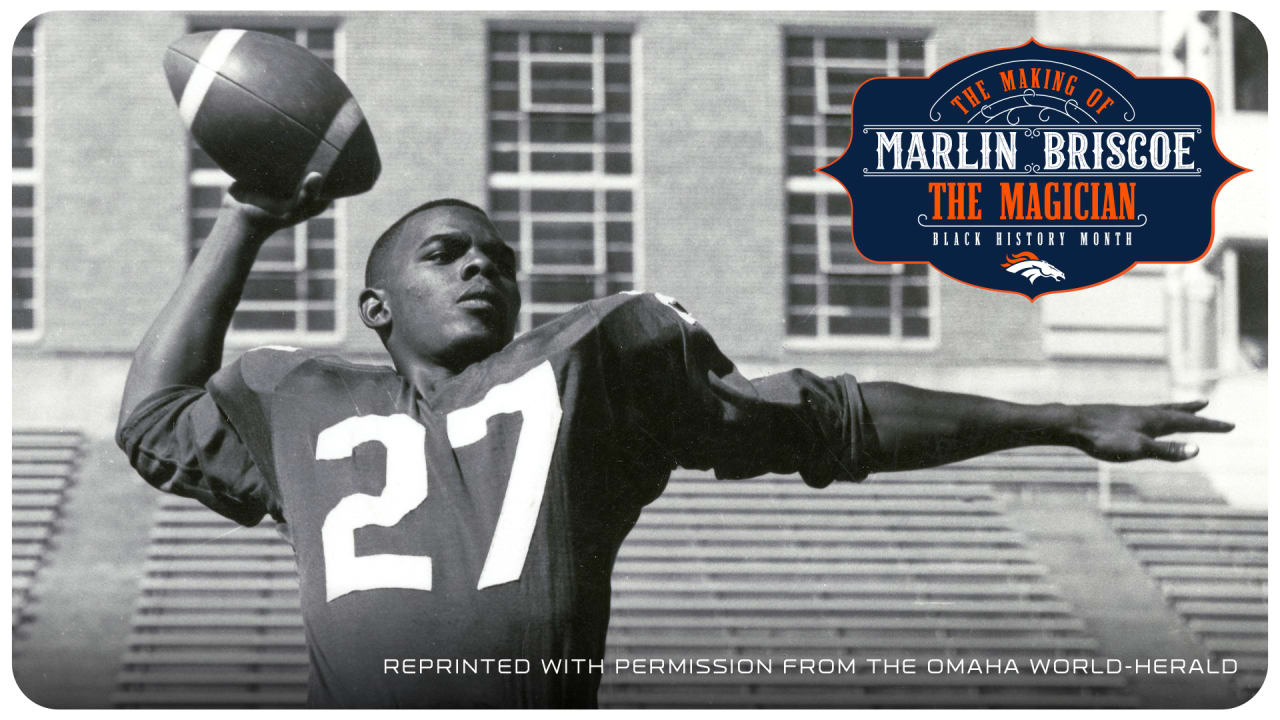

On Sept. 30, 1957, Marlin Briscoe's name appeared in his hometown newspaper for the first time.

Those paying attention to the Midget Football League's box scores that day[3] could see that the 12-year-old Briscoe had a nice game for his Ladcos team against the Mainliners. Briscoe helped lead a 48-0 rout with a 12-yard touchdown pass and two touchdown runs on a 50-yard sweep and a 5-yard plunge.

Over the next several years, Briscoe became a name to track in Omaha youth sports. In 1957, Ladcos earned a second-place finish[4] in their league. The next year[5], Briscoe threw two touchdowns to lead Highland School to a championship in a flag football league.

As he entered the high-school letterman ranks, though, Briscoe didn't have a clear path at the position at Omaha South High School. Another player his age, Joe Berenis, was noted for his accuracy as a quarterback, though the World-Herald also said[6] Briscoe "adds savvy at quarterback."

Two quarterbacks, one Black and one white. Aside from race, the two were quite similar. The World-Herald put both at 5-foot-8, with just 15 pounds separating the two in weight.

That 1961 season, the two juniors split time at the position, but for their senior year, Briscoe was asked to move to running back to replace their previous star halfback, who had just graduated. Briscoe was happy to do what was best for the team, but it rankled some in his neighborhood who wondered if there was more to it than just talent evaluation.

"I always had confidence in my ability," Briscoe says. "So I went on and played running back my senior year and went on to make all-city, and we won our division that year. So that was satisfying. My neighborhood thought it was a racist move because they knew that Joe and I would switch off through the years, our adolescent years. … But I was doing it for the good of the team."

Still, even though Briscoe didn't feel the sting of racism in that decision or in his days as a high school player, he could feel it when he stepped off the field and returned to life simply as a Black teenager.

That season, Briscoe played perhaps his finest game[7], scoring two touchdowns and recording two interceptions as a defensive back as he helped South break a 12-game losing streak to their rivals, who were rated as Nebraska's top prep team.

Afterward, Briscoe later recalled in an Associate Press story[8], he went to a bowling alley to grab a bite to eat.

"When we beat the No. 1 team in the state, I tried to get a sandwich there with a white guy," Briscoe said. "The man refused to serve me. He put the sandwich in a sack and gave it to me outside."

Even at a young age, he seemed to be accustomed to such discrimination.

"You just know how it is because you're black," Briscoe told the AP's Mike Rathet. "But I never let it worry me. There are good people and bad. My way is to show people what I am by performance. In essence, that's what it's all about."

His performance that season certainly drew admiration from his peers and coaches from around the city, as they voted to name Briscoe one of the 11 best players on the World-Herald's 1962 All-Intercity Team[9].

"An exceptional runner, this little fellow (5-9, 165) put the real sting into the South attack," Don Lee wrote for the paper. "A former quarterback, he was an expert passer, able to break up a game with a flip or two."

But Briscoe didn't view himself as a former quarterback — just a temporary running back. He had agreed to play halfback for the good of his team for that season; now that it was over, he wanted to return to the position he had otherwise played his whole life, but he didn't receive many suitors.

"Nobody would offer me a scholarship because they wanted me to play running back and I wasn't going to play running back," Briscoe says. I said, I want to play quarterback. So Al Caniglia, the coach at Omaha University at the time, he came over to my house and he said, Listen, I'll give you two things I'll do for you. First of all, you'll get an education, you'll get a diploma. And you can play quarterback. That's all I needed to hear."

Caniglia appeared to be a rarity in Briscoe's world — someone who saw his talent and potential as a quarterback, and someone who didn't care about the predominant way of thinking about what a quarterback should look like or how they should play.

"Al Caniglia was known as being certainly progressive for his time," Chatelain of the World-Herald says. "… Omaha University was not a dominant football program. I don't think they ever made any deep postseason runs or anything like that. But they were pretty progressive, and it wasn't just the football program. The wrestling program on campus had the first African-American coach at a [predominately] white university in the country. So, Omaha University was always sort of a progressive, activist type of place. And I think that's one of the reasons Marlin got a shot. … I mean he was only like 5-9, 5-10 so he probably wasn't like a natural Division I quarterback prospect.

"But I think Omaha and Caniglia recognized that he could really play."